Robert Longo. Untitled (Ferguson) Diptych, 2014. Photograph: Petzel GallerAfter writing about Robert Longo's drawing of Ferguson, in the previous post, I kept thinking of another battle painting featured on Amanda Vickery's The Story of Woman and Art, Lady Butler's 1874 Calling the Roll.

Robert Longo. Untitled (Ferguson) Diptych, 2014. Photograph: Petzel GallerAfter writing about Robert Longo's drawing of Ferguson, in the previous post, I kept thinking of another battle painting featured on Amanda Vickery's The Story of Woman and Art, Lady Butler's 1874 Calling the Roll.

Elizabeth Thompson, Lady Butler. Calling the Roll After An Engagement, Crimea, 1874. The Royal Collection, London.And this led me to John Singer Sargent's Gassed, of 1918:

Elizabeth Thompson, Lady Butler. Calling the Roll After An Engagement, Crimea, 1874. The Royal Collection, London.And this led me to John Singer Sargent's Gassed, of 1918:

John Singer Sargent. Gassed, 1918. The Imperial War Museum, London

John Singer Sargent. Gassed, 1918. The Imperial War Museum, London

From the Civil Rights Movement:

Martin Spider, Troopers charging marchers at the Pettus Bridge, Civil Rights Voting March in Selma, Alabama, March 7, 1965. Reproduced after: Steven Kasher, The Civil Rights Movement: A Photographic History, New York 1996, 179And lastly, because by this time it seems so obvious, the frieze on the entablature of the Parthenon:

Martin Spider, Troopers charging marchers at the Pettus Bridge, Civil Rights Voting March in Selma, Alabama, March 7, 1965. Reproduced after: Steven Kasher, The Civil Rights Movement: A Photographic History, New York 1996, 179And lastly, because by this time it seems so obvious, the frieze on the entablature of the Parthenon:

Entablature Frieze on the Parthenon, the Acropolis, Athens, Greece. 447-432 BCThere is something about the linear array of warriors that perhaps has its roots in the rendering of the endless wars – war as a permanent state of existence – between gods, states and cities of the eastern Mediterranean. Sargent's Gassed is an oil painting, but acts visually as a bas-relief: little depth of field here, and what is in the background is a smaller repetition of the foreground.

Entablature Frieze on the Parthenon, the Acropolis, Athens, Greece. 447-432 BCThere is something about the linear array of warriors that perhaps has its roots in the rendering of the endless wars – war as a permanent state of existence – between gods, states and cities of the eastern Mediterranean. Sargent's Gassed is an oil painting, but acts visually as a bas-relief: little depth of field here, and what is in the background is a smaller repetition of the foreground.

Lady Butler is known for a new sensitivity to the reality of war; conventional paintings of British heroism portrayed the heart of battles, all glory and snorting horses, rather than the ongoing grind of war. The Roll Call showed British soldiers in a state of extreme and weary collapse, after the battle, not in the battle. The Grenadier Guards are not shown in their full complement, but are crowded into a dark cluster of wounded spirit. This was the ordinary, unheroic side of war, a depiction unusual for its time. Now, I cannot find anywhere that says that Lady Butler actually saw a battle. Sargent was there, Longo wasn't, Martin Spider clearly held the camera. The painting is not necessarily a witness, rather it supplies a narrative needed, politically, by certain groups at the time. The nineteenth century British Army needed reform, mid-twentieth century America needed suffrage, The Great War needed an ending, early twentieth-century USA needs to re-examine the licence and the impunity given to its institutions of law and order.

The Parthenon frieze aside as it is included here for its formal structure, in all of these artworks we see the backs of men, the artist is a viewer from a distance, not gassed, not beaten, not weary. The men do not pose for the artist, or as is the unspoken intention, they do not pose for us, thus they do not accuse. That is left for the artist to do.

There is a horizontal datum line through the heads in these pieces, above is an empty air, below all is struggling uncertainty. There is no perspective, and perhaps no perspective can possibly justify these scenes. We are not asked to engage, the precision of the row exludes us, we are forced to simply gaze at the panoply, and this shocks us. And it shocks us into muteness because the subjects can't or won't hear us.

Monday, April 3, 2017 at 8:54AM

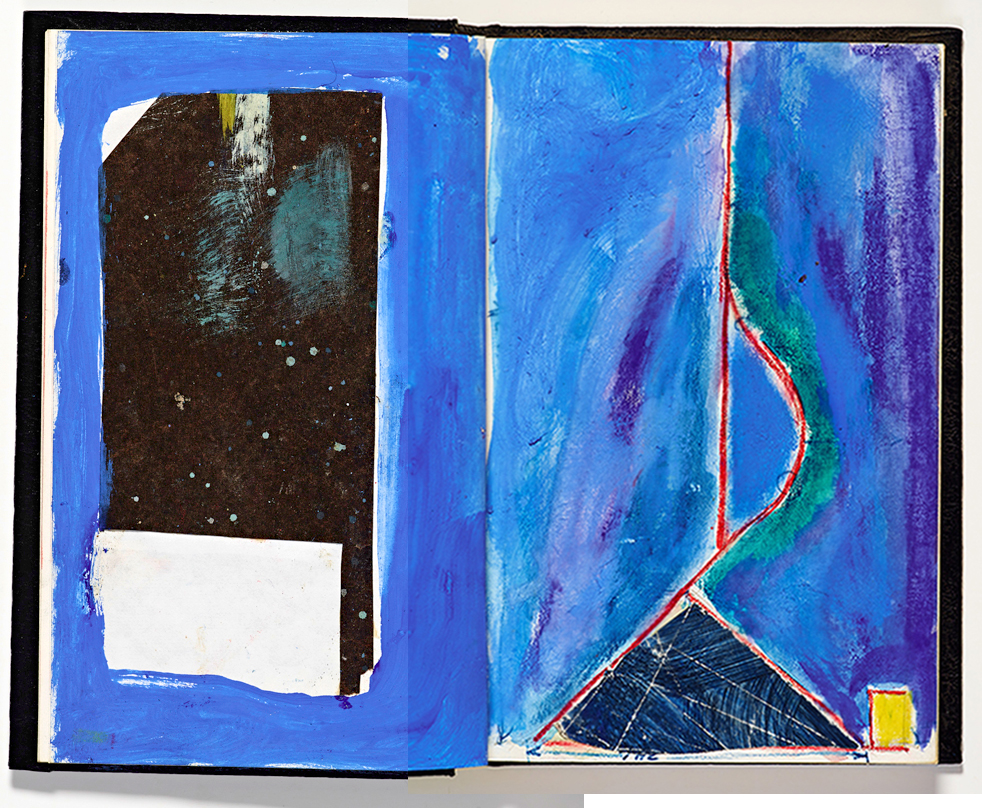

Monday, April 3, 2017 at 8:54AM  David Hockney sitting in the living room of his Malibu house, March 1988 Photo: © Condé Nast Archive / Corbis Artwork: © 2015 David Hockney

David Hockney sitting in the living room of his Malibu house, March 1988 Photo: © Condé Nast Archive / Corbis Artwork: © 2015 David Hockney David Hockney. Mulholland Drive: The Road to the Studio, 1980 acrylic on canvas, 86x243 in.

David Hockney. Mulholland Drive: The Road to the Studio, 1980 acrylic on canvas, 86x243 in. environment,

environment,  identity,

identity,  painting

painting