Richard Diebenkorn: Notebooks, 1943-93

Wednesday, March 1, 2017 at 9:37AM

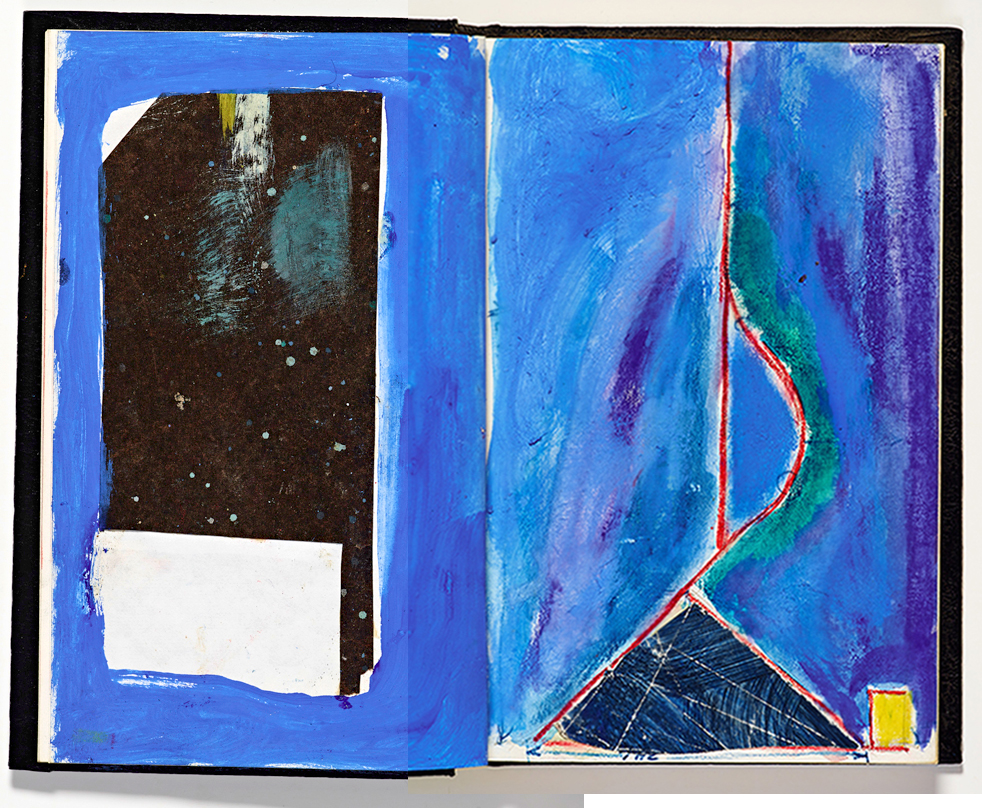

Wednesday, March 1, 2017 at 9:37AM  Richard Diebenkorn, “Untitled” from Sketchbook #2, pages 33-4 (1943–93), gouache, watercolor, crayon with graphite and cut and pasted paper on paper (gift of Phyllis Diebenkorn, © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation)

Richard Diebenkorn, “Untitled” from Sketchbook #2, pages 33-4 (1943–93), gouache, watercolor, crayon with graphite and cut and pasted paper on paper (gift of Phyllis Diebenkorn, © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation)

Alison Meier describes Diebenkorn's 29 sketchbooks as 'a sort of nomadic studio', an apt concept: the emergency kit for ideas, the travelling bank of lifesaving notes. They must have been everywhere as they are all listed as 1943-93, always in play, just grab a notebook handy and add a page or two. Nothing here indicates the notebook as chronological recording of one's development; there appears to be little reflection on one's art as continuum, nicely dated. No, these are simply files, unfiled, but like going through a box of unsorted slides: with each one the time, the heat, the place, all come rushing back.

It also says something, this disinterest in chronology, that all the work, the thoughts, the ideas, are on an equal footing. Early drawings, done with uncertain youth, are still around simply because they are in the notebook with the green cover, or the black spiral, or the one with the red paint on the outside; vaguely interesting, occupying a slim bit of notebook real estate next door to a vivid crayon thing done forty years later. Plus they might have an idea in them.

Painting is not like writing. The physical act of placing one word after another, and another, page after page itself is linear, sequential. Even the white space of concrete poetry contributes to the order of the poem, even erasures, crossings out and the reworking of writing disappear in print, usually its ultimate destination. Painting itself is a constant reworking of surface, three-dimensional, un-linear, a storm of marks that are never actually finished, rather they are abandoned. Famously De Kooning continually reworked his canvases, they were never finished, they are dated by duration. This quote, source unknown but found here, 'I paint this way because I can keep putting more things in it - drama, anger, pain, love, a figure, a horse, my ideas about space.' Have to trust what might be a dubious source, however, it says something about using the canvas as a notebook that keeps getting added to. Willem's notes on women.

Diebenkorn's notes on land. places. people. They have been given to Stanford by Phyllis Diebenkorn, a rather wonderful bequest that one can see here in an interactive display. museum.stanford.edu/diebenkornsketchbooks/

Richard Diebenkorn, “Untitled” from Sketchbook #16, (1943–93) (gift of Phyllis Diebenkorn, © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation)

Richard Diebenkorn, “Untitled” from Sketchbook #16, (1943–93) (gift of Phyllis Diebenkorn, © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation)